The last drop to stay below 2°C

No one doubts that oil production will go down in a 2°C world, but whether there is place for new oil fields is a far more nuanced discussion.

Oil sample from the Aldous field in the North Sea. Is more investment in oil consistent with climate policy? (photo: Anette Westgard – Statoil)

One of the most powerful narratives stemming from the carbon budget is that we can’t burn all known fossil fuel reserves. This is the common narrative, but I would argue it is not sufficiently nuanced.

If one has carbon capture and storage at scale, or carbon dioxide removal more generally, then the fossil fuel industry can have a relatively healthy future.

And carbon budgets are rather uncertain, a point that is rarely acknowledged, and different carbon budget estimates will allow the use of more or less fossil fuels.

While carbon budgets are effective for communication, they can oversimplify rather complex issues. It is better to base analysis on a range of emission scenarios, and look at how coal, oil, and gas may fare in a 2°C world.

The case for investing in new oil

One provocative conclusion from the Statoil Energy Perspectives 2017 is that huge investments are needed in oil production, even in a 2°C scenario. The basic story line is that existing oil fields decline faster than oil demand declines, and therefore new fields are needed to close the gap.

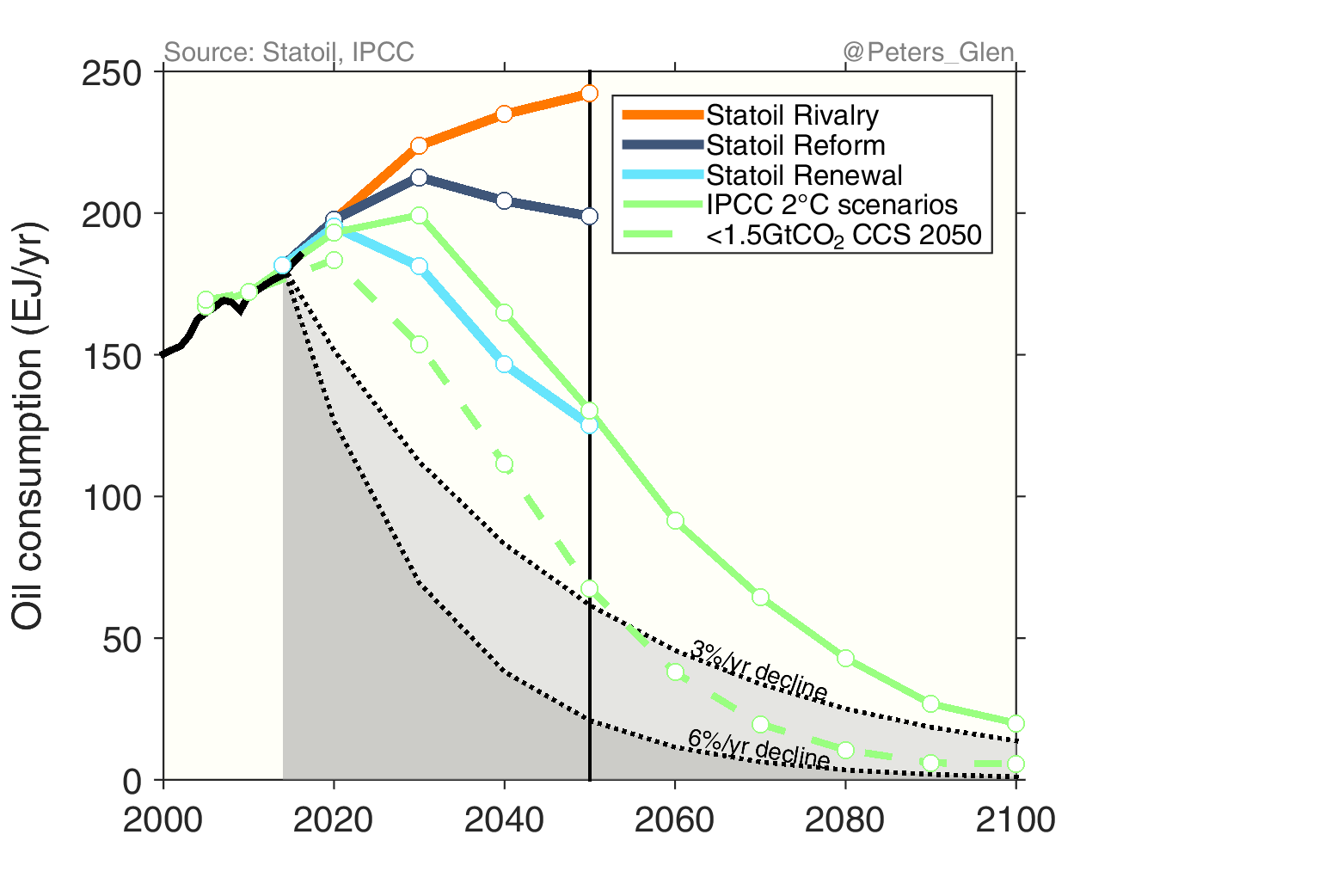

The argument is quite clear on a figure. Even though the decline rate of existing fields is crudely estimated at 3-6% per year, there is a clear gap between future supply and demand. Surely, we need more oil? Yes? No?

I am sure this figure and its narrative provokes many people, but it is a reasonable argument to make. It is also consistent with what the IEA and IPCC say!

It is possible to overlay the Statoil figure with the latest generation of scenarios from the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report. I have shown the median of the 250 or so scenarios that give a 50-66% probability of staying below 2°C, most comparable to Statoil’s Renewal scenario (& IEA’s 450 scenario). Other choices could be made (many favour a >66% probability), but I want to make a consistent comparison and not squabble about probabilities.

Statoil has comparable oil demand to the scenarios assessed by the IPCC, even though there will be variation across individually scenarios.

As I have argued before, the scenarios assessed by the IPCC use large levels of carbon capture and storage. Since it is such a critical component of many emission scenarios, I want to focus on that a little more here.

Perhaps a surprise to many, Statoil assumes rather low levels of carbon capture and storage. The IPCC scenarios have median carbon capture and storage in 2050 of 12 billion tonnes CO2, and a 10-90 percentile range of 6-19 billion tonnes CO2. The IEA World Energy Outlook has carbon capture and storage of around 3 billion tonnes CO2, and Statoil about half that (they do not report an explicit number). Yes, the IPCC is by far the most bullish on carbon capture and storage!

If we select the 50-66% probability 2°C scenarios with carbon capture and storage of less than 1.5 billion tonnes CO2 (14 scenarios in total), to be consistent with the value used by Statoil, then future oil demand will be lower, and oil demand declines more rapidly than in Statoil’s Renewal scenario.

This could suggest, relative to existing literature, Statoil’s oil demand is a touch on the high side. But, scenarios have a broad range, and Statoil’s renewal scenario is by no means inconsistent with the range of scenarios. Further, slightly higher oil demand by Statoil may be compensated by lower CO2 emissions elsewhere from coal and gas.

The requirements for new oil

The devil is always in the details!

Scenarios consistent of a set of assumptions on how the world may develop in the future, and for a given scenario to be (approximately) realised requires those assumptions to be realised.

What are some of the assumptions that Statoil needs to make to allow new oil production?

Carbon capture and storage: The above figures highlight one requirement for more oil and gas, a sufficient amount of carbon capture and storage (applied to coal, gas, bioenergy, or industry). In Statoil’s case, the world would need about 1.5 billion tonnes of CO2 processed by carbon capture and storage by 2050. This is about 1,500 facilities the size of the Sleipner field. This sounds big, but compared to others, Statoil is on the low-side when it comes to carbon capture and storage.

Coal consumption: Most scenarios require strong declines in coal consumption, and if they are not materialised then this leaves less space for oil in a 2°C world. In the case of Statoil, and consistent with many other scenarios, coal consumption declines at around 3% per year from today. Statoil’s Energy Perspectives does not paint a rosy picture for new coal production.

Gas consumption: Gas demand in the Statoil Energy Perspectives is similar to the scenarios assessed by the IPCC. In the Statoil Renewal scenario, gas consumption is heading down rapidly, and more rapidly than the average scenario assessed by the IPCC. As with oil, Statoil’s Energy Perspectives argues for new investments in new gas production.

Carbon dioxide: Coal, oil, and gas account for most carbon dioxide emissions, and the pathways from the Statoil Energy Perspectives, and scenarios assessed by the IPCC, are rather similar. Even though the Statoil Energy Perspectives has slightly different amounts of coal, oil, and gas, when weighted together using emission factors, the outcome in terms of carbon dioxide emissions is rather similar. This is expected, as both sets of scenarios aim for a 50% probability of staying below 2°C.

Non-fossil energy: In terms of non-fossil energy sources (nuclear, hydro, solar, and wind), the Statoil Energy Perspectives is broadly consistent with the scenarios assessed by the IPCC. I don’t want to go into the details on all other energy sources, but a few details are worth mentioning. Statoil has relatively low levels of bioenergy compared to the scenarios assessed by the IPCC. Statoil’s scenarios for solar and wind are currently tracking with current generation levels, and has steady linear growth from around 2020. Not good enough for some, but not that bad either!

Energy demand: The most surprising thing for me, is that the Statoil Energy Perspectives has declines in total energy consumption, particularly when compared to the scenarios assessed by the IPCC. Less energy demand, means less pressure on the energy system to supply additional energy. Overall, Statoil has less fossil fuel consumption because of the lower levels of CCS.

And, there is a big if, a big if.

Ambition: Will the world increase policy ambition to stay below 2°C? This is an important question. If the world does not mitigate sufficiently, then there will be more place for coal, oil, and gas. There will also be greater climate impacts. This is a decision the world will collectively need to make…

Do we want high or low oil prices?

Overall, I would argue that the Statoil Energy Perspectives gives a set of scenarios broadly consistent with the scientific literature, and certainly not biased in a way to put more emphasis on oil and gas. This would imply that Statoil should continue looking for more oil and gas…

Some argue oil companies should lead (or be forced to lead) by restricting investments in oil and gas exploration. Shutting down the oil industry may come with climate benefits, but there may also be some unexpected outcomes.

To state the obvious, meddling with the oil sector will changes prices and quantities. But, what is the optimal oil price (or production level) to best facilitate climate mitigation? This is a difficult question, and I don’t know the answer. But, as usual, I do have some thoughts!

If we underinvest in oil supply, then this may lead to high oil prices. If oil prices are over $100 per barrel, as an example, then that is a wonderful incentive for the oil industry to invest, regardless of climate policy. Policy would have to be extremely strong to overcome that financial incentive, and given history, I am not convinced policy makers would meet the challenge given government’s vested interest in tax revenues.

If oil demand is lower than we expect, or we overinvest in supply, then the oil price will be low. This will be a disincentive for investment in new oil and investments may instead be redirected to more profitable non-fossil technologies.

Behaviour will change in response to changes in oil prices, but I think this would be secondary compared to the supply-demand gap.

Yes, I am suggesting that it may be smart to invest in some oil to keep downward pressure on prices. This may suggest seeking out the most profitable oil reserves in the absence of subsidies.

I am sure I will get some heat for this suggestion, but we should accept that we don’t have a global dictator to implement the climate policies we might prefer. We have to thread the needle through a complex array of interacting factors and players.

A high carbon tax may shift investment away from the oil industry, but failing that, low oil prices may also shift investment away.

In the context of climate, we want to dampen investment in new fossil fuel resources. The way that it is done may not be so important…

Do we need more investment in oil?

I don’t have the answer. But, I would nevertheless argue it is not a black and white answer. The answer is complex and nuanced.

Back to the Statoil Energy Perspectives, they make a case for new oil and gas investments. This is premised on low future energy demand, rapid declines in coal use, a lot of carbon capture and storage, rapid growth in non-fossil energy, and clear guidelines on societies ambition to stay «well below 2°C».

Meet those criteria, and we can have more oil and 2°C! Don’t meet those criteria, then something has to give…

Oh, I didn’t answer the hard question. If we are to have more oil, whose oil should it be? Let’s save that discussion for another day, or as they say, «leave it to the market»…