Did 1.5°C suddenly get easier?

A new research paper suggests a rather significant upward revision of the carbon budget for 1.5°C. This is a potential game changer, but it is too early to reformulate mitigation plans.

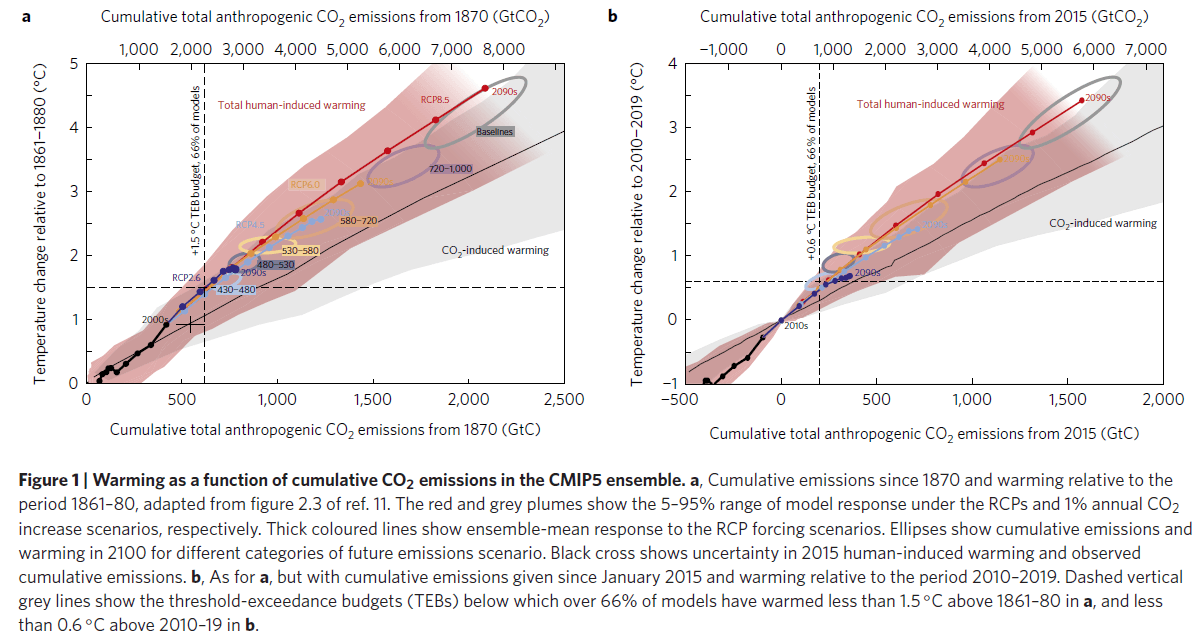

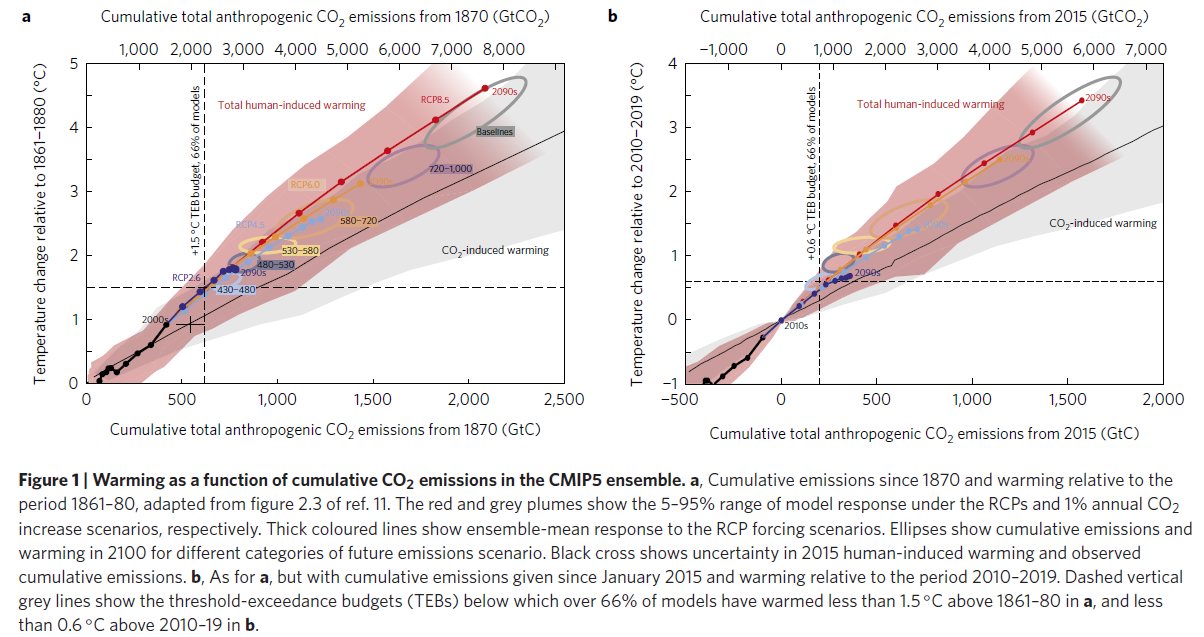

Figure: Millar et al, Nature Geoscience (2017).

The IPCC Synthesis Report suggests the carbon budget to stay below 1.5°C is about 250 billion tonnes CO2 from 2015, and at 2015 emission rates, the carbon budget will be gone by about 2022.

Surely, this must be wrong?

We are currently at around 1°C above pre-industrial levels (based on 1870), but can global average temperatures increase about 0.5°C in five years?

No! There is an obvious inconsistency with the carbon budgets, something I wrote about earlier!

A simple back-of-envelope calculation, with rounded numbers, helps explain the inconsistency.

We know that global average temperatures may increase as much as 0.25°C per decade, and that would mean it would take 20 years (two decades) to go from about 1°C today to 1.5°C. Since we emit about 40 billion tonnes CO2 per year, that would give a budget of about 800 billion tonnes of CO2 if we assumed emissions remained constant.

That very rough ball-park estimate of 800 billion tonnes of CO2, is much larger than the 250 billion tonnes CO2 suggested in the last IPCC report.

There must be an inconsistency somewhere (or a misunderstanding).

Resolving the inconsistency

As it turns out, the rough estimate of about 800 billion tonnes of CO2 is rather similar to the value presented in a new paper in Nature Geoscience, by Richard Millar and colleagues.

Using complex Earth System Models, Millar and colleagues find a carbon budget from 2016 to the year 1.5°C is crossed is 730 billion tonnes of CO2 when assuming no mitigation and exceeding 1.5°C (RCP8.5), and 880 billion tonnes CO2 from 2016 to 2100 when assuming strong mitigation and staying below 1.5°C (RCP2.6). Both these numbers are based on a 66% likelihood of exceeding or avoiding 1.5°C (technically, 66% of Earth System Model members of the CMIP5 ensemble).

Using a simple climate-carbon-cycle model, they find a likely budget range of 920-1980 billion tonnes CO2 to stay below 1.5°C, over the period 2016 to 2100 and with ambitious non-CO2 mitigation. The 66% likelihood is 920 billion tonnes CO2, but I would argue this is not comparable with the likelihood in the other budgets.

These carbon budgets are considerably larger than what was published in the last IPCC report, something I wrote about earlier. They are in fact more like what we thought was a 2°C carbon budget.

Did the IPCC get it wrong? Just let me leave that question hanging for a while…

While you ponder that question, it is worth noting that the authors of this paper developed the idea of carbon budgets, are the world leading experts on carbon budgets, and derived the carbon budgets in the IPCC process…

Richard Millar also has a guest post at Carbon Brief, which you should read.

What did the authors do?

The IPCC carbon budget for 1.5°C would seem inconsistent with observations, we are currently at about 1.0°C and for temperatures to increase 0.5°C by 2022 would seem impossible.

The new paper essentially makes this case,

«…[modelled] human-induced warming is over 0.3°C warmer than the central estimate for human-induced warming to 2015″

To deal with this apparent inconsistency, Millar and colleagues shift the axes of the well-known model-based IPCC cumulative emission figure. The figure below shows the original figure (left) and the updated version (right).

Instead of starting the models in 1870 and hoping they line up with observations in 2015, they shifted the origin of the figure to 2015, so observations and models agree. The clock is reset to 0°C in 2015.

To determine the warming from 1870, they use only the warming attributed to anthropogenic activities (ignoring volcanoes and solar variability), which they estimate as 0.93°C based on Otto and colleagues and reconfirmed in this study.

They also change the preindustrial baseline to 1861-1880, instead of 1850-1900. The change in baseline makes a small difference, but others have suggested changes in the opposite direction.

The shift of the axes makes a world of difference. It makes the stars align. The budget is now consistent with when we expect 1.5°C to be reached, in 20 or so years!

While one could argue the pros and cons of a shift in axes, the shift makes the carbon budget to exceed 1.5°C consistent with expectations.

But, this is not the full story, because we want to stay below 1.5°C.

Staying below 1.5°C

The carbon budget to stay below 1.5°C requires a different definition, and hence, it is a different story…

Some of the paper’s authors have previously argued that the carbon budget to stay below a given temperature threshold should be smaller than the carbon budget to exceed the threshold. This is also what I have found earlier across a range of scenarios and models.

Millar and colleagues find a larger carbon budget to avoid 1.5°C, an inconsistency I don’t know how to resolve. And it is the carbon budget to avoid 1.5°C that matters for climate policy.

The implications

The implications of this paper are breath taking. No, I am not exaggerating. And the implications are to do both with politics and with science.

For politics, the stakes are high. Just ponder these two potential outcomes:

- Suppose the paper is correct, then 1.5°C is a distinct possibility, about the same effort that we previously thought for 2°C. There would be real and tangible hope for small island states and other vulnerable communities. And 2°C would be a rather feasible and realistic option, meaning that I would have to go eat some serious humble pie.

- Suppose we start to act on their larger budgets, but after another 5-10 years we discover they were wrong. Then we may have completely blown any chance of 1.5°C or 2°C.

I seriously hope they have this right, or at least, I hope they will be vocal if they revise their estimates downwards!

For science, I can’t help but frame the paper in two ways:

- We understand the climate system, but a more careful accounting shows the carbon budgets are much larger.

- We don’t understand the climate system.

I have written a lot about carbon budgets in the past (Blog posts: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, Commentary, Papers 1, 2, plus other bits and pieces), so I feel rather confident of my understanding. But, I am a small fish compared to the authors of this paper.

On the first point, I already have serious reservations with the IPCC carbon budgets, mainly because of uncountable inconsistencies. Since the authors modify something I don’t really trust in the first place, then I am a little cautious of the findings. But, if the climate system behaves as we thought, then careful accounting should allow us to reconcile the difference between the original and updated carbon budgets. Science has made progress.

On the second point, the paper is going to have ripple effects. If their adjustments are correct, then those adjustments may cause inconsistencies elsewhere. Do we have the climate sensitivity wrong? Some argue that committed warming and aerosols would push us over 1.5°C. My mind boggles at the potential implications if the second point is realised.

Because the political and scientific implications of this paper are so immense, it will need a rigorous assessment by the scientific and policy communities. That is going to take time, perhaps years.

Science is slow. Blogging is not, and I will come with a few technical comments in the next week or so.

What about 2°C?

Millar and colleagues do not discuss carbon budget for 2°C or «well below 2°C« as in the Paris Agreement. Some may argue this is a rather important omission.

I have argued previously that 0.5°C makes a big difference to the carbon budget, and this is consistent with the IPCC carbon budgets.

One would expect that the difference between 1.5°C and 2°C carbon budgets would be consistent with earlier work, and rather importantly, this follows directly from the linear cumulative emissions relationship.

The updated 1.5°C is more like what we expected for 2°C, and thus the updated 2°C carbon budget is probably more like we expected for 2.5°C.

Given that the emission pledges submitted to the Paris Agreement are somewhat around 2.5°C to 3°C across most studies, then the updated carbon budgets would imply 2°C is roughly consistent with the current emission pledges.

This is something that will make policy makers happy, but let’s hope they have these numbers right!

What to do in the short-term?

Whilst the carbon budget is a brilliant concept, it has many challenging issues as outlined in my previous posts (find them here).

The carbon budget concept is a brilliant way to illustrate the importance of zero emissions, the need for rapid mitigation, and to compare different temperature targets. We need it for that.

The carbon budget concept is less useful for emission pathways, particularly with tight carbon budgets and given that it is possible to exceed the carbon budget using negative emissions.

The IPCC consensus view indicates the carbon budget for 1.5°C is around 250 billion tonnes of CO2 from 2015.

Millar and colleagues suggest budgets of 730 billion tonnes of CO2 (RCP8.5), 880 billion tonnes CO2 (RCP2.6), and 920 billion tonnes CO2 using a simple carbon-carbon-cycle model, for carbon budgets from 2016 with a 66% likelihood.

Another study on 1.5°C emission pathways, finds the carbon budget over the period 2010-2100 is between 0-400 billion tonnes of CO2, which would be -200-200 billion tonnes CO2 from 2015-2100.

This gives carbon budgets for 1.5°C over 2016-2100, often from the same authors, ranging from -200 to 1000 billion tonnes of CO2. What a mess!

One thing this paper has convinced me, is that the carbon budget concept is just simply too uncertain to be of any practical use in policy. A point I made last year.

What do I tell a policy maker?

It is best to say we need net-zero emissions by 2050 to 2100, as specified in the Paris Agreement. Problem solved, carbon budget not needed!